Should we get rid of the plural you guys because it’s sexist? Joe Pinsker, writing in theAtlantic, reports a growing resistance to the common use of you guys—along with hey guys, and just plain guys—to address mixed groups of men and women, as well as single-sex groups of only women. Pinsker finds that trans and gender-nonconforming people feel excluded by you guys; that teachers and business people reject you guys as not inclusive; and that lots of people want to ditch you guys in favor of something gender neutral, like folks, or people, or comrades.

Then Pinsker adds this peculiar observation by way of explaining why you guys is so popular: “English lacks a standard gender-neutral second-person plural pronoun.” He actually says this twice.

But that is flat-out wrong. English has always had a gender-neutral second-person plural pronoun: you.

You has been the second-person plural pronoun since the days of Old English. You has always been everyone’s second-person plural, from Beowulf to both the Queens Elizabeth (or if you prefer, both the Queen Elizabeths). It’s the second-person plural for Joe Pinsker, and it’s the second-person plural for me and you as well. It’s singular you that’s the newcomer.

When English started out, when the Angles and the Saxons and the Jutes left their continental homes and crossed the Channel, and Theresa May and Boris Johnson weren’t around to stop them from immigrating, they brought with them a bunch of continental pronouns, including the second-person singular thou, and the second-person plural you. By the fourteenth century, speakers of English started using you as a polite or deferential singular: a peasant might call a knight you, for example, and the knight, in turn, would take the peasant’s crops and call the peasant thou, just to emphasize the power dynamic and to remind the peasant of the vast social gap between them.

Here are two other examples of English plural pronouns used as singular: the royal we,or in countries without a monarchy, the editorial we. And singular they, which appears in English writing as early as the fourteenth century.

By the seventeenth century, singular you started to appear not just as a polite form, but in every context, and singular thou and the other th- forms, thee, thy, and thine, began to disappear. By the nineteenth century, that changeover was all but complete, andthou, they, and thy were relegated to regional or dialect speech, where they remain. For example, in D. H. Lawrence’s novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928) Mellors, the gamekeeper, uses tha when he’s in bed with Lady Chatterley, while she uses singularyou to him. Because in England, the words you use reflect your social class, even during sex. We still use thou, thee, and thy today in standard English, but only jokingly to sound old fashioned—it’s so faux Shakespearean.

So if you has been plural for 1,500 years, what accounts for the popularity of you guys? And why did it become universally popular at the same time that another masculine form, generic he, went stake-through-the-heart dead? Because in modern English, the second-person plural and the second-person singular are the same word: you, and that creates the possibility for ambiguity: are you (one, single person) talking to me? or areyou (a whole bunch of people, plural) talking to me? Apparently, the need for a clearly and unambiguously plural you trumps the desire to be gender-inclusive, and so, for most people—not for everyone—either guys has lost its gender-marking, or what marking it may retain has become no big deal.

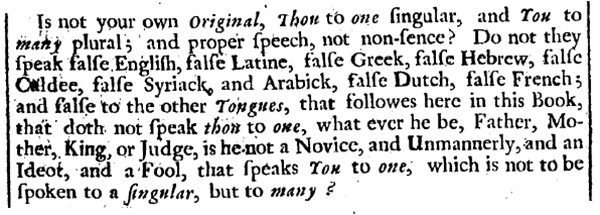

Back in the day, not everybody approved of the upstart singular you, but that didn’t stop the form from taking over. In 1660, George Fox, better known as the founder of the Society of Friends (the Quakers), wrote a whole book railing against singular you. Fox called anyone using you instead of thou an idiot and a fool.

George Fox, A battledore for teachers and professors to learn singular and plural, 1660.

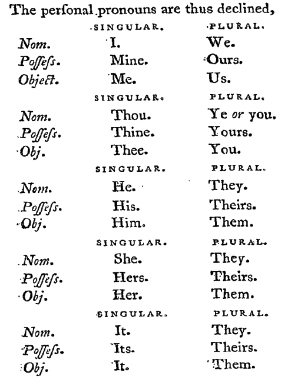

Nobody paid attention to Fox’s objections. They were too busy using singular you. Yet for two centuries grammar books continued to teach that thou was the second-person singular, and you, the plural, and teachers expected students to write thou on grammar tests, even though students were using singular you when their teachers weren’t looking, and the teachers used singular you when the students weren’t around.

Pedantic to the end, Lindley Murray insisted on singular thou, plural you, in his popular school grammar

But singular you wasn’t the last change for the second person pronouns. Not even close. Once you became solidly singular as well as plural, people began to assume that ambiguous you was basically a singular pronoun—that’s Joe Pinsker’s assumption in hisAtlantic piece—and when they wanted to be extra clear that they were using a plural, they invented the new plurals y’all, youse, and you’uns. But like thou, thee, and thybefore them, these new pronouns carried the stigma of nonstandard or regional use. They were confined to the spoken language, not considered suitable for formal, written English.

Gender-specific masculine you guys first appears in the 1890s, but in the 1960s and 1970s, gender-neutral you guys starts popping up as well. You guys has always been informal, but unlike y’all, youse, and you’uns, it was never regional. Yes, some people in the ’70s and ’80s thought it was objectionably sexist—but apparently not being regional was a big enough plus that most people didn’t worry about the sexism part, and you guys began its gradual takeover as the emphatic second-person plural in informal, spoken English. It’s not marked for region. It’s not marked for class. It’s not marked for level of education.

But pronoun evolution wasn’t done. People in the American south began to use y’all ambiguously to refer to one person as well as groups of people. Y’all became a polite singular, like you back in the fourteenth century. There are still some southerners who insist that singular y’all is an error introduced by carpetbaggers. Even when confronted with proof, they refuse to acknowledge that any real southerner would ever use singular y’all. They explain that the user is really a Yankee. Or that yes, the good ole clerk at the Gas-N-Go was clearly addressing one person—you can see it on the CCTV tapes—but by saying “y’all come back” they meant you (the person addressed) and all your friends and relatives—it was an implied plural. But enough people must be using singular y’all that it’s triggered yet another disambiguating plural, all y’all. And so at least for now, all y’all is about as unambiguously plural as a second-person pronoun can get. But unlike you guys, all y’all is still a regional form.

So what about the new campaign to oust you guys? Campaigns against particular idioms don’t work well. They didn’t work for George Fox. By the time he began his protest against singular you, it was already too late to stop the change. For more than a century, schoolteachers have waged a campaign to eradicate ain’t from English. They managed to stigmatize the word, but ain’t is still going strong. Campaigns don’t stand much of a chance of ousting you guys, either. Grammar shaming may make people feel bad about their language use. It may make them self-conscious. Or reluctant to speak. But it won’t change what people say or write, and if they’re determined to say you guys, then they’ll continue to say you guys. And if they want to go with a new second-person plural, they’ll do that too. Just don’t count on the new plural being folks, or people, or comrades. Or peeps. I mean, peeps? really?