Singular they has become the pronoun of choice to replace he and she in cases where the gender of the antecedent—the word the pronoun refers to—is unknown, irrelevant, or nonbinary, or where gender needs to be concealed. It’s the word we use for sentences like Everyone loves their mother.

But that’s nothing new. The Oxford English Dictionary traces singular they back to 1375, where it appears in the medieval romance William and the Werewolf. Except for the old-style language of that poem, its use of singular they to refer to an unnamed person seems very modern.

Here’s the Middle English version:

Hastely hiȝed eche . . . þei neyȝþed so neiȝh . . . þere william & his worþi lef were liand i-fere.

In modern English, that’s,

Each man hurried . . . till they drew near . . . where William and his darling were lying together.

Since forms may exist in speech long before they’re written down, it’s likely that singular they was common even before the late fourteenth century. That makes an old form even older.

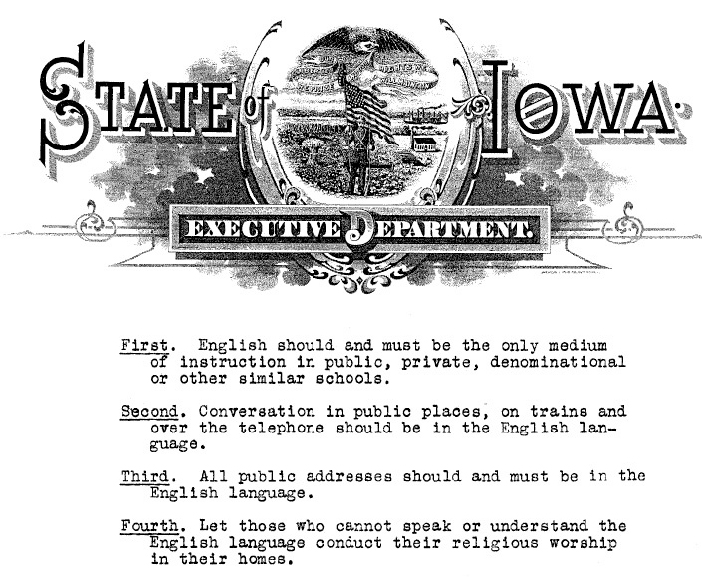

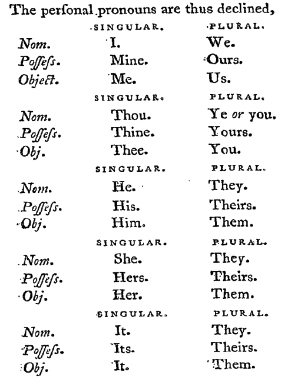

In the eighteenth century, grammarians began warning that singular they was an error because a plural pronoun can’t take a singular antecedent. They clearly forgot that singular you was a plural pronoun that had become singular as well.

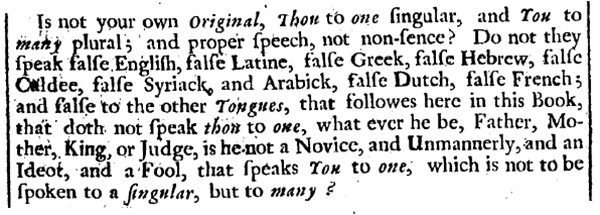

You functioned as a polite singular for centuries, but in the seventeenth century singular you replaced thou, thee, and thy, except for some dialect use. That change met with some resistance. In 1660, George Fox, the founder of Quakerism, wrote a whole book labeling anyone who used singular you an idiot or a fool. And eighteenth-century grammarians like Robert Lowth and Lindley Murray regularly tested students on thou as singular, you as plural, despite the fact that students used singular you when their teachers weren’t looking. It’s a sure bet that teachers used singular you when their students weren’t looking. Anyone who said thou and thee was seen as a fool and an idiot, or a Quaker, or at least hopelessly out of date.

In 1795, Lindley Murray’s popular grammar textbook still insisted

that thou was singular, you, plural.

Singular you has become normal and unremarkable. Also unremarkable are the royal we and, in countries without a monarchy, the editorial we: first-person plurals used regularly as singulars and nobody calling anyone an idiot and a fool.

Singular they is well on its way to being normal and unremarkable as well. Toward the end of the twentieth century, language authorities began to approve the form. The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) not only accepts singular they, they also use the form in their definitions. And the New Oxford American Dictionary (3e, 2010) calls singular they “generally accepted” with indefinites, and “now common but less widely accepted” with definite nouns, especially in formal contexts.

Not everyone is down with singular they. The well-respected Chicago Manual of Style still rejects singular they for formal writing, and just the other day a teacher told me that he still corrects students who use everyone . . . their in their papers, though he probably uses singular they when his students aren’t looking.

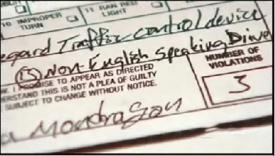

In 2017 a transgender Florida school teacher was removed from their fifth-grade classroom for asking their students to refer to them with the gender-neutral singular they. And in 2015, after the Diversity Office at the University of Tennessee suggested that teachers ask their students, “What’s your pronoun?” because some students might prefer an invented nonbinary pronoun like zie or something more conventional, like singular they, the Tennessee state legislature passed a law banning the use of taxpayer dollars for gender-neutral pronouns, despite the fact that no one knows how much a pronoun actually costs.

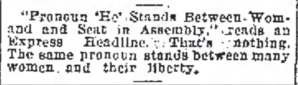

It’s no surprise that Tennessee, the state that banned the teaching of evolution in 1925, also failed to stop the evolution of English one hundred years later, because the fight against singular they was already lost by the time eighteenth-century critics began objecting to it. In 1794, a contributor to the New Bedford Medley mansplains to three women that the singular they they used in an earlier essay in the newspaper was grammatically incorrect and does no “honor to themselves, or the female sex in general.” To which they honorably reply that they used singular they on purpose because ”we wished to conceal the gender,” and they challenge their critic to invent a new pronoun if their politically-charged use of singular they upsets him so much. Apparently all words and no action, the grammar pedant did not do so. More recently, a colleague who is otherwise conservative told me that they found singular they useful “when talking about what certain people in my field say about other people in my field as a way of concealing the identity of my source.”

R. W. Burchfield, in The New Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1996), dismisses objections to singular they as unsupported by the historical record. Burchfield observes that the construction is “passing unnoticed” by speakers of standard English as well as by copy editors, and he concludes that this trend is “irreversible.” People who want to be inclusive, or respectful of other people’s preferences, use singular they. And people who don’t want to be inclusive, or who don’t respect other people’s pronoun choices, use singular they as well. Even people who object to singular they as a grammatical error use it themselves when they’re not looking, a sure sign that anyone who objects to singular they is, if not a fool or an idiot, at least hopelessly out of date.